March 23, 2021

A Fork in the Road for Traditional Banks

In our first three articles, we offered some thoughts on the strategic choices that go into making a company “API-first,” the market forces with which APIs contend and the direct impact those choices have on achieving SaaS-like unit economics in a market hurtling toward verticalizing the end-user value chain.

The next two articles will focus on how these forces play out in financial institutions and the future of banking itself and start to answer the question: who's got APIs, who's writing to them, and who's actually at risk of being SOL.

Read all seven parts here:

Part 1: APIs are Everywhere — An Intentional Choice: Being API First

Part 2: On APIs and SaaS Unit Economics

Part 3: On Market Power — Who Reads, Who Writes, Who’s SOL

Part 4: A Fork in the Road for Traditional Banks

Part 5: Impacts of BaaS Intermediation on Embedded Finance

Part 6: API-first development: fuel for regulations, Open Banking and Standardization

Part 7: The No-Code/Low-Code Accelerant

To state the obvious, the fintech revolution exists in a state of tension with traditional financial institutions.

On one hand, scores of fintechs are dominating the banking experience without...being banks. Call them synthetic banks, or banking apps or financial assistants, these fintech companies are the new face of what it means to 'bank' for millions of consumers. Grab any 20-something off the street and ask them if Chime, Betterment, Remitly, Current or Albert are banks and I bet you my lunch money they'd say yes...ish. And, of course, the fact that Varo and Lending Club actually now arebanks, makes the consumer perception all the more confusing.

To be fair, these apps are usually beautiful, slick, reliable and immersive and increasingly sticky as they roll out additional credit, lending and P2P services. Users can get what they need, trust what they get, and ensure that their day-to-day interactions with money 'just work.'

Many of them seem to be making some tangible progress with un/underbanked populations, and the data show clear progress from a peak in 2011 to a recorded low in 2019. In the QED portfolio, Current’s data suggest that more than 40 percent of its customers have never had a bank account before.

On the other hand, getting a banking charter is hard—the vast majority of fintechs can't live without the institutions responsible for deposits, lending, reserves, treasury and the slew of monetary and fiscal mechanisms responsible for stability, solvency and liquidity. Nonetheless, the market has now unbundled the question of who owns the customer versus who runs the stack.

Let's map it out:

- Top-of-stack fintechs are trying to capture more of the customer experience through horizontal growth. In this layer, though they can be criticized as mere “marketing arbitrage” or customer experience layers, they are engaged in a constant battle on customer features and trying to build brand loyalty. Many of them are also now thinking about trying to "become banks" and verticalize downward, reaping the benefits of payments systems, deposits, and federal support.

- Banks face classic incumbent dilemmas with their existing customer bases, existing processes, and their existing revenue. Moreover, many bank executives are mystified by the sloppiness of the fintechs that are nonetheless running away with the show. Mostly, we see banks engaging in the new front of customer experience competition and feature expansion—sometimes by launching their own, sometimes by acquisition, sometimes by partnership.

But both of these paths are not so easy, and the mechanisms for partnership seem fraught with peril. There are many small banks that have decided to make fintech a strategy – these are sponsor banks. They focus on delivering access to the privileges of a bank charter to the various technology companies that want to compete for customer’s attention. But for larger banks, who think of themselves as having valuable brands and valuable customer relationships, to embrace the sponsor bank strategy seems like accepting a future where banks are nothing more than “dumb pipes.”

(NB: We think the dumb pipe argument is not strictly correct and is a lazy explanation for what’s going on elsewhere in the stack. More on this in Article 5 next week, but in short form: Dumb Is Relative. Banks have competed for hundreds of years with pricing, risk appetite, treasury, risk management/execution and customer service. It may be true that many banks become ‘infrastructural’ over time as more consumer-facing functions migrate elsewhere, but it’s unlikely that such banks will completely become vestigial organs. You wouldn’t call AWS a dumb pipe, would you?)

So, the tension comes down to whether the bank wants to—or even can—develop and maintain its own set of APIs and whether it survives by becoming an API-first bank (colloquially, a headless bank) or merely being a bank that happens to have APIs to support partners.

Much like we've seen years ago in the move from on-prem bare metal to cloud, is there a path for some banks to become commoditized backends for the apps that own the consumer experience? (Shout out to Ben Thompson over at Stratechery, who drew a similar comparison to cloud applications running on commodity hardware).

As we'll see, the larger money center banks have the critical mass (both in terms of market power and the sheer volume of IT resources) to pursue an imperfect platform play whose APIs are written to, whereas the uncertain fate of regional and community banks rests in their ability to become infrastructure or channel partners.

Money center banks — Resources to platform

The large money center banks often have homegrown core systems, thousands of engineers on payroll and billion-dollar IT budgets. They are large enough that even FISer, Jack Henry and the like will do what it takes to win a deal. (Frankly, even SaaS market leaders like Salesforce would think twice before rejecting a customization request from a JPMC or HSBC).

But crucially, money center banks are increasingly deploying capital and resources to clean house—to rebase core systems and get everything under one roof, i.e. wrap existing technology in modern APIs and become a platform for third parties. Why? They recognize the verticalization of fintech, the enormous TAMs that live outside their direct control, and so they all want to ensure they have a place at the bottom of lucrative stacks that would be too expensive to monetize in a vacuum.

Any money center bank that has stable APIs and a strong technological foundation is eligible to serve as the foundational FI and reap their cut of the revenue via interchange, credit, accounts themselves or some other mechanism.

In other words, sticking with our framework, the money center banks with critical mass and the IT heft to match will evolve into companies whose APIs are written to. They may not have APIs that are up and running today, but they are likely to get there. And when they interact with other companies of comparable scale, the business negotiations will play out as they always have.

Community banks — Bundle to survive

On the other end of the spectrum we have community banks—the many thousands of small local institutions and pillars of communities that have for so long functioned in quite an analog way. And even though it’s customary to think of community banks as small businesses (which they often are), they loom large in the communities and economies where they operate— comprising 99 percent of all banks, providing more than 60 percent of small business loans and numbering more than 50,000 locations nationwide.

As the consumer experience gravitates toward extra-bank fintech apps, we have to ask: will community banks be SOL?

Community banks have rich relationships with their local user groups and disproportionately trend toward in-branch interactions. But inevitably these consumer patterns will digitize. Customers who don't need their bank to be down the road may go elsewhere for their banking needs; those who stay will expect modern experiences and services. How can these institutions play catch up if we don't expect them to develop their own APIs?

Ultimately, community banks are small enough to survive as long as they have a real strategy. One that starts by acknowledging what they’re actually good at and outsourcing the rest to tech players who want to partner to access the banking system.

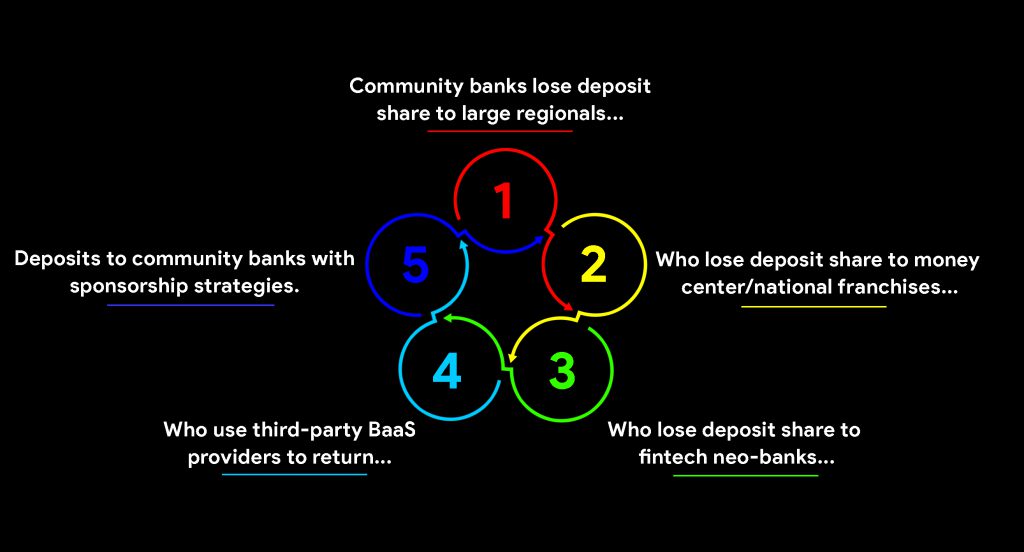

Community banks need to consider what options they have for bundling services provided by third parties—an organ transplant of sorts. For deposit gathering in particular, this means a major cultural and recruiting shift toward operating more as a tech channel partner than a bank per se. The main mindset shift? Outsource as much as possible to focus on the community enablement and leave most of the banking to someone else. It does suggest a bit of a matryoshka doll or franchise effect: "Main Street USA Community Bank, powered by Chime (powered by Bancorp)". Alternatively, we could call it the circle of (deposit) life:

More importantly, community banks have two sides of their balance sheet. While 2020 made clear that deposit gathering is no longer a branch-driven marketplace, there’s still plenty of room for community banks to compete on asset generation—small business loans, commercial real estate, agricultural lending and local industry specific services leave plenty of room for local knowledge, and real people to add value and win. In fact, even their assets are commoditized (like consumer unsecured lending), partnerships to drive local awareness and local loyalty can have material halo effects.

However, in practice, both fintech startups and mature API players looking to gain market share by sustaining community banks will be very choosy about how much effort they will expend to add a community bank as a partner or how much they are willing to adapt their product roadmap to accommodate legacy systems and processes.

Regional banks — Stuck in the middle of the barbell

Regional banks will find this framework most challenging. Large regional banks in the U.S. are large public companies, have tens of thousands of employees, hundreds if not thousands of IT personnel and typically have strong cultural preferences for building their own systems rather than buying from others. These preferences mean that they have the cultural attributes of companies whose APIs are written-to, but they do not necessarily have functional APIs, workable plans to have APIs, or (and this is the hard truth) necessary technical talent to implement an API-led strategy on their own as market dynamics around them are shifting very quickly.

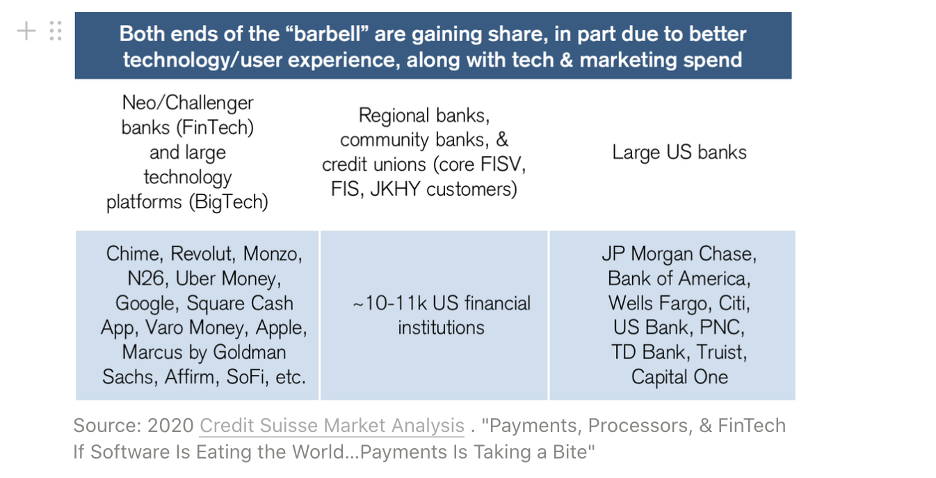

As with community banks, regional banks find themselves in a disappearing middle, or the middle of a "barbell" according to one Credit Suisse market analysis:

Source: 2020 Credit Suisse Market Analysis . "Payments, Processors, & FinTech: If Software Is Eating the World…Payments Is Taking a Bite"

Historically, regional banks have remained large, powerful customers who can dictate terms with almost all their vendors. But as consumer- and SMB-facing fintech companies continue to demonstrate smooth and repeatable networks of integrations regardless of whatever "actual bank" sits underneath, regional banks’ market power continues to erode.

We can be reasonably certain that regional banks will not try to face these challenges head on—we don’t expect them to hire hundreds of developers for the purpose of integrating their legacy systems to a network of potentially valuable technology companies. hey don't want to have to write to other company's APIs if they can avoid it. But because of this, these companies are at significant risk of falling out of luck entirely.

Strategically, regional banks should take advantage of their relative comfort and strength in today’s market conditions to change the way that they partner. In particular, this means that banks need to measure how easy it is for new vendors to do business with them and treat that measure as a significant business objective. Every bank in the country has a unique, complicated legacy tech stack. And in almost all cases, every way in which these tech stacks are unique destroys rather than creates value.

However, if (big if):

- these banks keep large enough customer populations to provide mutual benefit between themselves and new consumer-facing players

- they are appropriately incentivized to wrap core banking services in partner-friendly APIs

- they are targeting some of the same markets as consumer-facing fintechs (but the fintechs simply do it better)

- then opportunities arise for the banks to reach additional customer segments indirectly as infrastructure partners with new fintechs.

What will PacWest do, now that it has partnered with Treasury Prime to deploy APIs—will it collaborate with neobanks or big tech? Will it partner on deposits, payments or lending? A bank balance sheet is an economic super power—banks can create money! They can borrow money subsidized by the U.S. government! Emigrant Bank uses this superpower to now underwrite Brex; BBVA Open Platform sits under Wise to support SMB banking. Numerous financial institutions are writing those playbooks right now—a pattern is emerging. It’s certainly a trend, but how far will it go? Well, we'll see.

For now, large regional banks will continue to pressure vendors and partners to absorb the costs and the pain of these unique projects. Startups take the pain of 24-month sales cycles and custom integrations as the cost of doing business. But bank executives and stakeholders absorb those costs indirectly through vendor due diligence and change management. In turn, vendors charge more than they might if the sales cycle were short, in order to make their unit economics make sense. But it does beg a question: as ecosystem participants try to get more pluggable, will the nature of partnerships move from transactional to collaborative? Will we see more joint software-development projects come out of regional banks and emerging fintechs?

Maybe. But as we'll see in the next article, the proliferation of Banking-as-a-Service and the evolving role of embedded finance is a very visible middleman that will shift how banks apply their effort to participating in a rapidly changing ecosystem.

**

Amias Gerety is a partner at QED Investors, a leading fintech venture capital firm. His investing has focused largely on back office and infrastructure themes. Prior to QED, Amias was Acting Assistant Secretary for Financial Institutions in the Obama Administration.

Nate Soffio is an MBA Candidate at Wharton focusing on fintech, regulation, and financial inclusion. There, is the co-chair of Wharton’s Fintech Conference taking place April 22-23. Hailing from Stamford, CT by way of Medellin, Colombia, he spent a decade building (and breaking) things in the infrastructure and regtech worlds with a focus on Know-Your-Customer and identity management. Before Wharton, he helped lead product at Arachnys, a London-based regtech and QED portfolio company. Nate holds a B.A. with Distinction in Linguistic Anthropology from Yale University. In his spare time you can find him road cycling, rock climbing, and cooking.

Media inquiries:

Ashley Marshall, Director PR and Communications, QED

Ashley@QEDInvestors.com

(518) 577-9984